Parchmenting

The art of parchment-making is still alive in Ethiopia, and is practiced primarily by the scribes who will write on the finished product. Skins of goats are used for books, while those of sheep are preferred for scrolls. In the past, the skins of horses are known to have been used, producing large amounts of parchment, but provoking some condemnation, as horses are unclean animals to Orthodox Ethiopians. The selected skins are soaked in water for a few days, then, when thoroughly soaked, the skin is stretched on a frame, and tensioned. Meat and connective tissue is scraped off with the curved parchment knife, then the pumice stone (sometimes in concert with an abrasive powder) is used to more finely clean the skin. After being washed, the frame is put up against a tree or the side of a house, to dry in the shade. The tension will be checked, and increased, over the day or more it will take to dry. This process of drying under tension is what makes parchment different than leather, as the fibres of the skin are re-arranged into a denser, more durable sheet. Once the stretched skin (now unfinished parchment) has dried, it is scraped with the parchment adze to remove the hair follicles, and rubbed again with the pumice-stone, to clean off all of the epidermis and much of the “grain” layer. Once this is done, it is washed again and set out to dry for a final time; when totally dry, it may be cut out of the frame, and is ready to be used.

In contrast to historical techniques elsewhere in the Christian world, the Ethiopian scribe does not use slaked lime as a depilant, relying on clean water to loosen the hair.

Parchment-making is an ancient process, and was probably known in Ethiopia before the coming of Christianity. However, the Church showed an early preference for writing its books on parchment, and, as religious material was the primary type of book production during the medieval period, in Ethiopia as in Europe, parchment was standardized as the material of choice from c. 200 C. E. until the wide-spread adoption of paper.

The Tools

The Parchment Knife

[mäqad or መአፈፊያ ካራ määfäfiya kara] Used to separate fatty subcutaneous tissue from the skin layer on the flesh side; some use in other tasks. When removing flesh, it is used at an angle of perhaps 30 degrees from the plane of the skin.

The Parchment Adze

[የብራና መፋኪያ yäbǝranna mäfakiya mäträbiya] A modified version of a woodworking adze, it is dragged along the skin at a 90° angle, to scrape off the hair, epidermis, and “grain” layer.

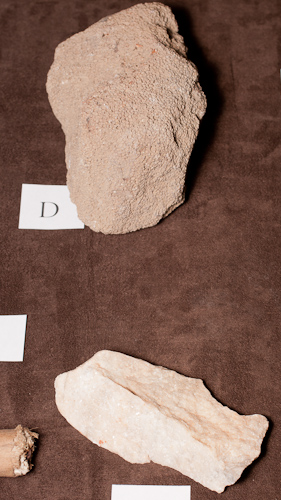

The Stones

Two stones are used in parchment-making, a pumice-stone (መራመሚያ ድንጋይ märamämiya dǝngay), used to scour the skin clean, sometimes with the assistance of an abrasive of powdered calcite or marble, called (ኆጸ hoṣa).

The Frame

The Process

- Cutting holes for the rods.

- Inserting rods on each edge.

- Tensioning rods to frame.

- Removing fat and tissue with parchment-knife.

- Scrubbing with pumice and abrasive.

- Removing hair with parchment-adze.

- Appearance of finished surface.

- Scrubbing and washing.

- Sewing holes and tears shut.

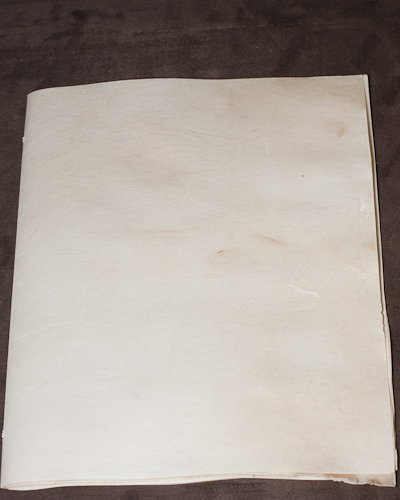

The Finished Product

A bifolium of parchment, ready for writing. The smoothness and lack of hair follicles on this side marks it as the flesh side, as opposed to the hair side, which would show the remains of the follicles and generally retain more dirt and oil.

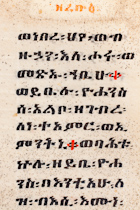

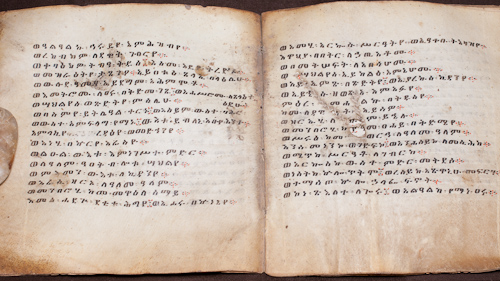

Single quire from the Dawit (Psalms)

Ge'ez. 160 x 173 mm. Work of Tsegaeab GebreMaryam, 20th century.

An example of a finished page showing evidence of repairs. Open to part of Psalm 98 (The Lord becomes king; let peoples grow angry!).